Quantum computers on the way to simulate quantum chromodynamics

Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the fundamental theory for how quarks and gluons interact through the strong nuclear force, for example, to bind quarks into larger subatomic particles like protons and neutrons, and also holding nuclei together. QCD is a non-abelian SU(3) gauge theory, where the 3 refers to red, green, or blue "color charge" of the quarks and gluons. A prominent feature of QCD is color confinement: The strong force gets stronger with distance. Under normal conditions, it is hence impossible to pull quarks apart; they always form color-neutral combinations like the three differently colored quarks in a proton. Only at extremely high energy densities, matter undergoes a phase transition to a quark-gluon plasma which existed shortly after the Big Bang.

In their recent paper "The phase diagram of quantum chromodynamics in one dimension on a quantum computer", QLab researchers Alaina Green and Norbert Linke, their team, and collaborators from the University of Waterloo and York University show a fascinating path for the simulation of QCD at finite temperatures on quantum computers. The study has been published in Nature Communications [Nat. Commun. 16, 10288 (2025), arXiv:2501.00579].

The breakthrough: Using ion vibrations to realize thermal states

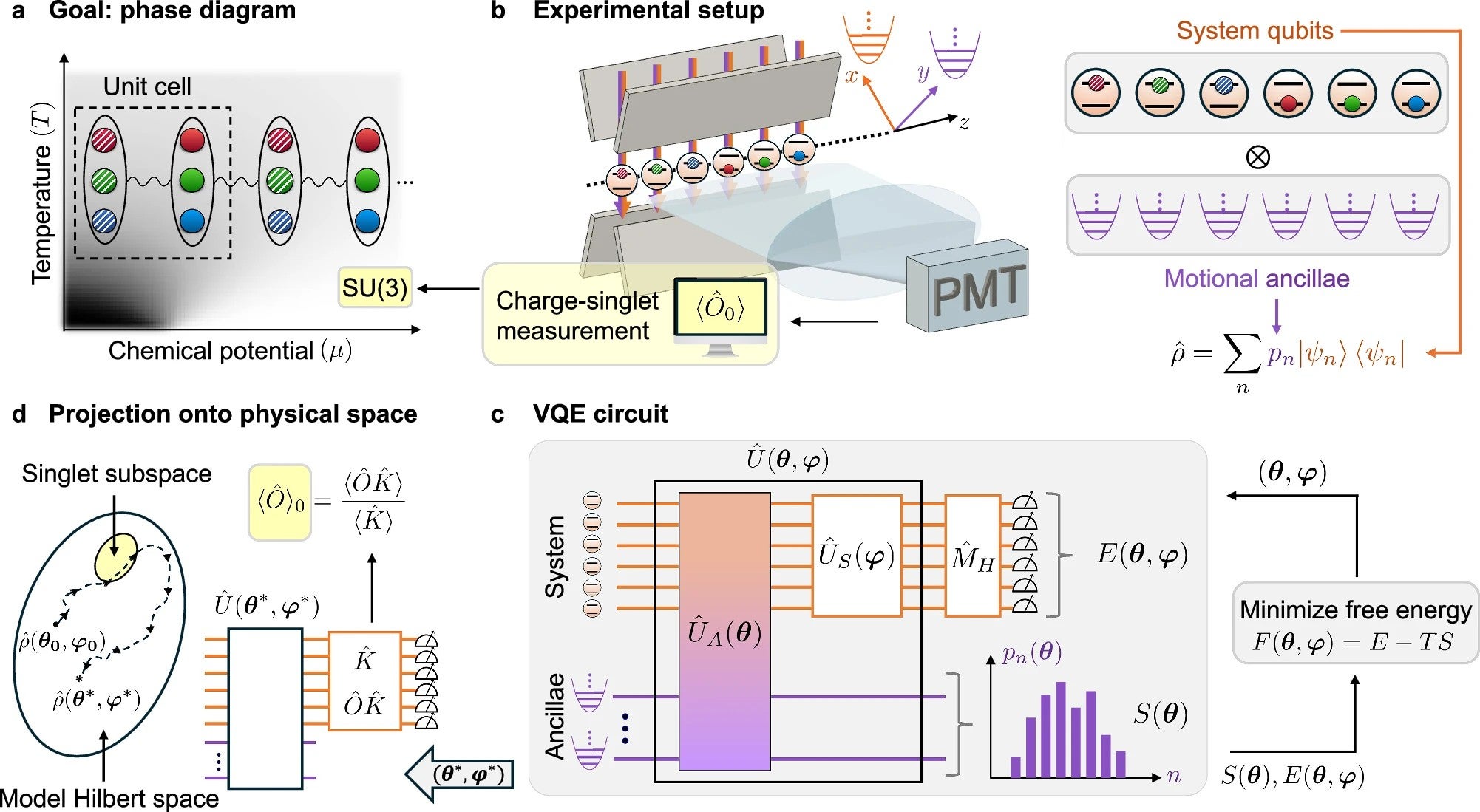

The team utilized a trapped-ion quantum computer, where individual atomic ions are suspended in space by electromagnetic fields and manipulated with lasers to serve as qubits. To simulate the complex thermal states of quarks, the researchers employed two innovations:

- Motional ancillae: Instead of just using the internal energy levels of the ions as bits (qubits), they leveraged the vibrational modes (the "jiggling") of the ions in the trap. These vibrations acted as an extra "hidden" register of information, allowing the team to prepare thermal states much more efficiently without needing a massive increase in the number of qubits.

- Charge-Singlet Measurements: The researchers developed a measurement technique to ensure their simulation always obeyed color neutrality.

Specifically, hyperfine-split electronic ground states of $^{171}$Yb$^+$ ions were used as qubits, motional modes in the y-direction served as thermal ancillas, and motional modes in the x-direction were used to implement entangling gates between the qubits. Qubit and motional operations were driven by a set of laser beams, and the qubit states are measured through fluorescence imaging. The team prepared thermal equilibrium states of a small QCD unit cell using a variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) protocol, applying quantum circuits that entangle the motional ancillas with the qubits and qubits among themselves, then optimizing the circuit gates to minimize the free energy. Finally, they measured the chiral condensate density with a clever scheme to project to the charge-singlet sector.

"This work pioneers the quantum simulation of QCD at finite density and temperature," the authors conclude, "laying the foundation to explore QCD phenomena on quantum platforms."